The popularity of different video game genres has wildly shifted throughout the last decades. Developers picked up advanced technologies and paired them with game design ideas that hadn’t been challenged before, which very often led to the rise of a new star ─ or rather star constellations ─ at the video game firmament. In two articles released earlier this year, we talked about the massive impact of Half-Life and Counter-Strike, the logical conclusion of the successful amalgamation that were the early 90s modding scene and infamous first person shooters like Doom and Quake.

However, if you were actively playing video games in the final decade of the last millenia, chances are you came across a massive array of popular strategy games, some of which still seem to shape or at least thoughtfully impact the modern video game landscape. Westwoods Dune 2 is the hallmark name that took the world by storm, establishing the term real time strategy game seemingly overnight. Before we talk about Harkonnen, Sandworms and Spice, it makes sense to lay some groundwork to establish our knowledge, similar to a windtrap on Arrakis.

Putting a focus on strategy games might seem odd, given that neither the sale charts nor active concurrent players seem to reflect a heightened interest for the genre. But – Dota 2 and League of Legends, both MOBAs or multiplayer online battle arenas, with millions of active players and a cult followership, are both a product of the golden era of real time strategy games. Starcraft and Starcraft 2, and, to a smaller degree, Warcraft 3, are dominating factors of the global esports scene. Professional players of Starcraft and Starcraft 2 enjoy a cult status in South Korea, similar to prominent athletes of European football leagues.

A distinction has to be made between different types of strategy games. The top level can be roughly divided into turn-based and real-time strategy, which naturally include vastly different reaction times and thought processes for the players involved. It’s interesting to note that this article, published for GameSpy in 2004 argues that, although you have more time to think in a turn-based game, you also have to deal with a stronger artificial intelligence due to the processor also having more “time to think”. This might be a relic from the past but it greatly serves as a real-world analogy to multi-tasking.

Finally, when games like Utopia (1981) and Stonkers (1982) blessed their audience with new and innovative ways to play against an “AI”, it wasn’t initially called real-time, let alone strategy. These titles were still considered action games by name, because everything that has been labeled strategy before ─ like the 1980s game Computer Bismarck ─ was played in turns. Therefore, action strategy was born and Utopia is generally seen as the grandfather of the real-time strategy genre.

The waters became even more muddled when The Ancient Art of War was released in 1984. It is considered as one of the earliest precursors to both real-time strategy and real-time tactics games. Think of it like this: If you’re on a journey, your strategy is the overall plan or route to reach your destination, while tactics are the turns you take, the speed you drive, or the stops you make along the way. The distinction between RTS and RTT is often subtle. RTS games typically involve resource management, base building, and large-scale strategy, while RTT games focus more on the tactical aspect of combat without the overarching strategic elements.

The Ancient Art of War involved selecting and moving troops, and engaging in battles with enemies in real-time on various terrains. There’s no base-building or resource management, which are hallmark features of many later RTS games. Instead, the game centers more on the tactics of warfare, influenced by the writings of Sun Tzu. Given its early place in the evolution of strategy video games, it’s seen as a foundational game that has elements of both genres but it paves the way for RTTs like Myth (1997) or the Total War Series (2000).

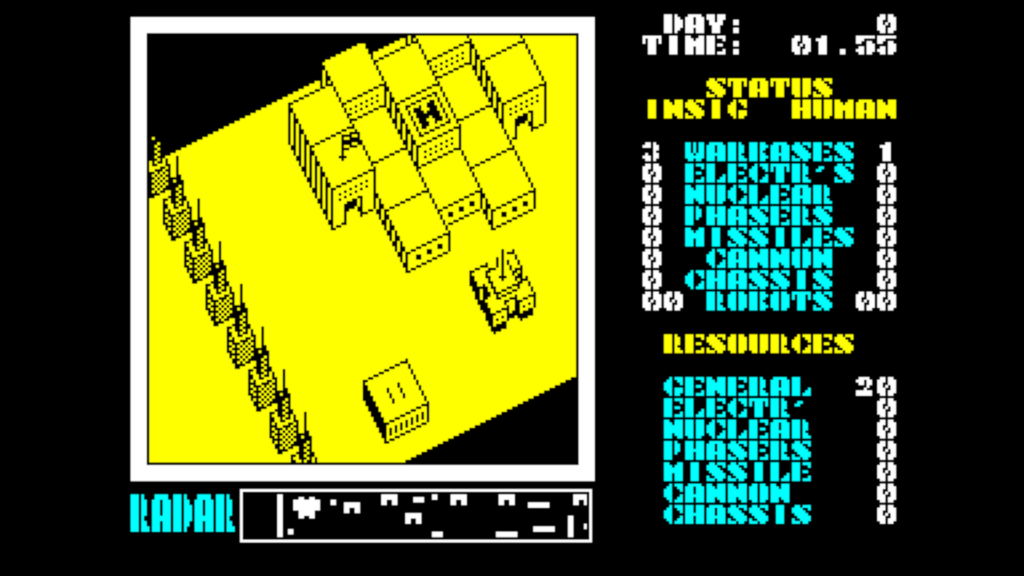

A rather unusual title called Herzog Zwei was exclusively published on the Sega Mega Drive in 1989. While it wasn’t strictly an RTS in the way that later games like Dune 2 or Command & Conquer were, Herzog Zwei laid down many foundational elements of the genre. Players control a transforming mecha, which can shift between an aircraft and a ground combat form, transport units, engage in direct combat, and command other units around the map. Herzog Zwei was also notable for its split-screen two-player mode, an unusual feature for strategy games of its time because it allowed for direct player-versus-player action, fostering competitive gameplay.

Although it often doesn’t receive as much recognition in mainstream gaming discussions, it’s a title that significantly influenced the evolution of the RTS genre and gained a cult following in Japan, the only market in which it gained real commercial success. More importantly, it planted seeds for the RTS genre’s development. Several developers, including those behind Dune 2 have acknowledged the game’s impact. Which brings us to Westwood Studios.

While most famous for Dune II and the Command & Conquer series, Westwood’s journey before its dive into the deserts of Arrakis, was filled with interesting strategy and role playing games. Founded in 1985 by Brett Sperry and Louis Castle, the duo would find its home in different franchises. Eye of the Beholder (1991) is a classic Dungeons & Dragons landmark title that is frequently listed as highly influential. It stood out for the atmospheric graphics, compelling gameplay, and faithful adherence to D&D rules.

The Crescent Hawk’s Inception (1988) was an RPG, while its sequel The Crescent Hawk’s Revenge (1990) leaned more towards real-time tactics, foreshadowing Westwood’s future trajectory; both were based on the Battletech tabletop universe. The real-time elements in BattleTech: The Crescent Hawk’s Revenge hinted at Westwood’s growing interest in real-time gameplay and the game’s combat, although primitive, was an early indicator of the studio’s direction. As Westwood’s reputation grew, so did its collaborations.

As the 1990s began, Virgin Interactive secured the rights to make a game based on the Dune franchise. Given Westwood’s growing reputation and experience with real-time gameplay, they were a natural choice to develop the project. Initially conceptualized as a blend of adventure and strategy, the game’s direction shifted dramatically during development, although these elements could be found later in the “unfortunate” predecessor Dune. A great game in itself, developed by Cryo Interactive and also published under Virgin Interactives license, it would ultimately be overshadowed by the massive success of Dune 2.

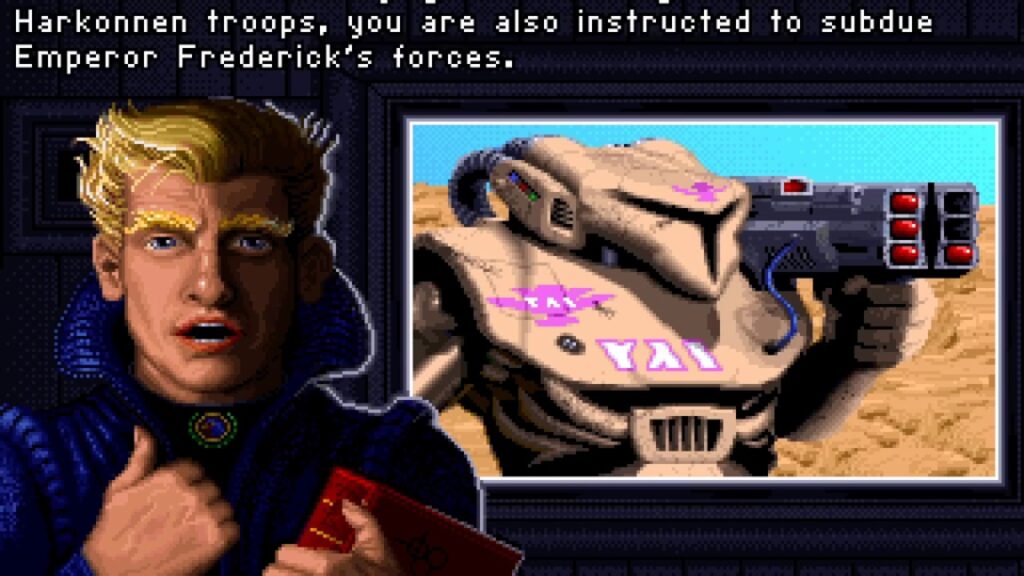

Dune II derives its thematic content from Frank Herbert’s celebrated sci-fi novel, Dune. While Westwood took creative liberties with the story, the game revolves around the conflict between three houses Atreides, Harkonnen, and Ordos, as they battle for control of the desert planet Arrakis and its invaluable spice, melange. Each house has unique attributes, units, and playstyles, providing nuanced asymmetric gameplay. The brutal Harkonnen would offer powerful but slow and expensive units, a stark contrast to the light and swift Ordos, who played more like scouts or infiltrators. The counter-system of unit vulnerabilities and strengths encouraged unit diversity and tactics.

At its core, Dune 2 introduced real-time strategy mechanics that the genre still adheres to today. Gathering resources, building bases with structures such as construction yards and refineries, researching technology upgrades along branching trees, training diverse combat and support units, and battling in real-time feel oddly familiar even if you’d never played it before. The game’s mouse-driven interface was groundbreaking. Players could select units, give orders, and manage their base using the mouse, a departure from the turn-based or keyboard-driven games of that era. However, it wasn’t yet possible to assemble multiple units into a group, which could turn a big battle into a rapid clickfest. The minimap provided a top-down view for panning and waypoints and animated unit sprites conveyed action and damage visually. Dune 2‘s UI set the gold standard that RTS games hence utilized, for the better or worse.

Ambient synthesized music crafted an atmospheric soundscape fitting of the stark, mysterious desert planet Arrakis and voice samples transmitted radio chatter between factions vying for control and the valuable spice Melange. Mission briefings, inter-house politics, and plot twists embedded players deep into the heart of the Arrakeen conflict, portrayed with the help of cinematic cutscenes. The list of innovations and exceptional features would go on and on but the point made should be clear by now. While other games tinkered with real-time strategy mechanics, Dune 2 is lauded as the title that truly birthed the RTS genre.

In fact, Brett Sperry, producer of Dune 2, tried to come up with words to describe the game they were just working on. He used the term “real-time strategy”, which not only stuck with Dune 2, but a whole genre that should follow in its wake. This was merely a new dawn for plenty of games that had yet to come but it marked the beginning of the most successful decade for strategy titles. Which is odd, considering the fact that the most popular games today offer some kind of online mode ─ or no single player at all. Meanwhile, Dune 2 didn’t even have a multiplayer option. Though absent, the RTS mechanics it championed would become central to multiplayer gaming in subsequent titles and ultimately lead to their demise, apart from a handful of outstanding exceptions.

Dune II forever shaped real-time strategy and video game history overall, rightfully earning its reputation as an iconic and pioneering title. It demonstrated that real-time strategy was a vibrant, compelling genre that could captivate players while having enormous potential for competitive multiplayer gameplay between human opponents, at least in the near future. Selling over 100,000 copies rapidly, Dune II became a breakout hit for Westwood Studios.

The studio would follow up with the famous Command & Conquer series but before that happens, another developer would enter the stage and establish a series of RTS that, building on Arrakian foundations, is going to take the world by storm ─ or rather, a Blizzard. However, this is the end of our first part about real-time strategy games that notably influenced the genre, the modding and online gaming scene. Next week, we’re leaving Arrakis to set foot on Azeroth, where the RTS genre branches from sci-fi to high fantasy.