Our ongoing series puts the spotlight on games that moved the multiplayer genre forward, sending ripples through the video game industry with intersections to server hosting and online gameplay: Doom, Half-Life, StarCraft, DayZ and many more; they all initiated an evolutionary process that moved the medium videogames into new territories, spawning genres and multiple, spiritual successors along the way. Today, it’s time to talk about the real vanguards of online gaming: Massive Multiplayer Online Role Playing games, or short MMORPGs. Despite their decline in popularity in terms of absolute numbers for new releases, established MMOs from years past continue operations due to their persistent online nature and active player bases.

Reigning kings like Final Fantasy XIV and World of Warcraft have been around for one or even two decades respectively, mastering the art of sailing through stormy waters where other companies suffered shipwreck. However, we’re getting ahead of ourselves, already talking about games that run with 3d graphics, in-game purchases and monthly subscriptions in the millions. Also, being online today is not only a convenience to play online games and stream hit series; it has become a necessity in our daily lives, from buying bus tickets on your phone to meeting your coworkers in Teams, Meets and whatnot. Back when online games started to attract a viable audience, the internet wasn’t even a meaningful word. So before people were busy thinking about how to engage in multiplayer games online, they first had to solve the “multi” part.

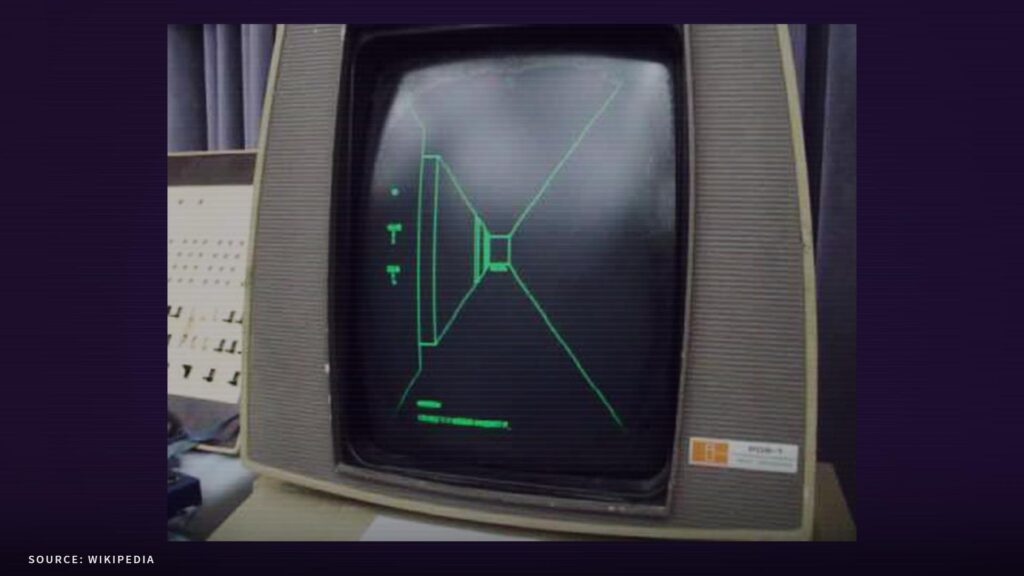

At this point, it’s common knowledge that Tennis for Two is the grandfather of video games. Two indicates that at least a pair of people were able to play together, or rather, against each other. This wasn’t going to change when Atari created Pong in 1972, a “modernized” version that, due to its hardware, is often referred to as the very first true video game. However, players back then were looking at the same screen. This would change with the creation of MazeWar in 1973, which allowed for two different computers to be connected and played on. Two different players hunted each other through a maze, shooting on sight.

Simplistic in design, this was one of the very first ego shooters and, while not entirely obvious, a cornerstone for multiplayer online games. The appeal of early networked gaming stemmed from the drive for social experiences and competition. Players enjoyed not just competing against programmed AI enemies and high scores, but directly testing their skills against thinking human opponents, collaborating and communicating toward shared goals. It transformed gaming into a more relatable and lively activity between people. Later versions of MazeWar, also called MazeWar 3D, allowed for even more simultaneous players, yet there was a catch: MazeWar wasn’t commercially released but played in universities and institutes that offered the computing power and equipment needed. Even more important: these faculties were often connected via ARPANET, an early computer network that served as a critically important foundation for the eventual creation of the internet.

The beginning of the ARPANET traces back to the late 1960s, when the United States government organization called the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) began funding research into computer networking. At the time, computers were large mainframes that were very expensive. Operating and connecting them together into a long distance network would be far more efficient than operating them all independently. Established links between universities allowed transfer of data over long distances using a technology called packet switching: messages were broken into smaller packets, dispatched over available lines and reassembled on the receiving end. Obviously, this also worked for video games. Our next important term was coined in the 70s, putting another piece to the online gaming puzzle.

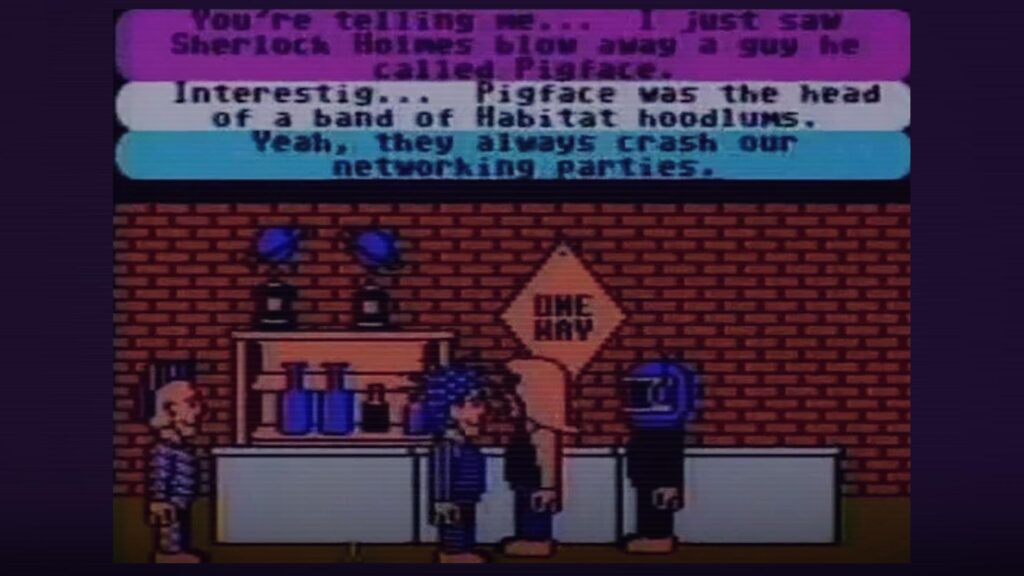

Games like MazeWar were played by many people but neither were they confronted with role playing problems nor, as a matter of fact, any kind of relevant storytelling. This is where MUDs come into play, short for Multi User Dungeon. These text-based adventures let players explore fantasy realms and battle monsters by reading textual descriptions and typing commands. MUD1, likely the first and therefore eponymous for other written dungeons, was created in 1978 by Richard Bartle, inspired by a dungeon version of the famous text adventure Zork. MUD1 established many gameplay tropes like leveling up a character through battling monsters in an imaginary realm described through text. Other early influential MUDs included Island of Kesmai, which focused more on virtual world persistence and graphically rendered characters.

MUDs proliferated through the 1980s within university network circles as both entertainment and educational programming exercises and various MUD platforms arose like MUSH and MOO which customized the MUD concept for roleplaying and community building. AberMUD, released in 1987, made the MUD experience easier to access. It introduced a more intuitive command parser and gameplay features like popup menus, which naturally increased the appeal for less tech-savvy users. Furthermore, TinyMUD, created in 1989, allowed players to build and extend the game world themselves by modifying rooms, creating quests, and establishing new realms – an early version of user-generated content and the possible starting point for future modders. In 1990, another type of MUDs, called DikuMUD, was created by a group of Copenhagen based university students led by Sebastian Hammer.

DikuMUD was based on AberMUD code and open source, allowing it to be freely distributed, modified, and expanded upon. Codebase aside, DikuMUD moved in a quite different direction compared to what other MUDs tried to achieve with their focus on storytelling and worldbuilding. Instead, it focused heavily on hack ‘n slash combat mechanics and gameplay, introducing guilds and PvP battles years before MMORPGs. Key DikuMUDs included SMAUG, Merc and CircleMUD, which refined and built upon the core mechanics of hunting, leveling up equipment and skills through combat. While not as user-friendly as AberMUD or feature-rich as TinyMUD, DikuMUD left a major impact through its hack ‘n slash gameplay DNA and open source legacy powering derivatives and future MMORPGs.

In the early 1990s, single player games did tend to have more advanced graphics capabilities compared to multiplayer titles. There are a few key reasons for this: Rendering detailed 3D visuals was extremely demanding at the time. Multiplayer games had to divide limited processing power between multiple simultaneous players/environments, constraining graphical capabilities. Additionally, multiplayer networked gaming was still quite new, with developers focused more on getting the underlying connectivity and synchronization right first. This in turn meant that polishing graphics took a backseat. Budgeting was another point, simply because major studios poured more resources into flagship single player titles. We all know that popular games like WarCraft and its Science Fiction sibling StarCraft are soon going to change this, but for now multiplayer was a niche pursued by smaller teams with more limited budgets.

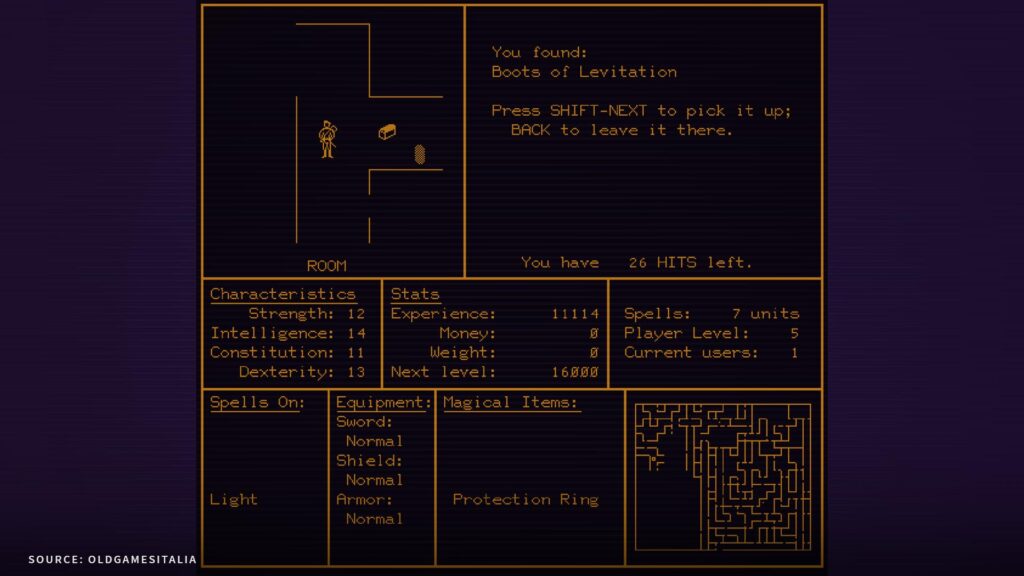

Multiplayer gaming initially required expensive connections to university networks, whereas single player games could be accessed more widely as standalone experiences. The standardization of TCP/IP, affordable Home Internet Access and the growth of lan parties helped mitigate ─ even nullify ─ the disadvantages of creating a multiplayer title. The final explanation for why multiplayer titles, up to this point, had worse graphics compared to their single player counterparts might be rather simple: audience expectations. Early multiplayer gamers were used to using their imagination to fill in blanks for text-based MUDs, even writing and drawing their own maps and handbooks. Flashy visuals were not yet a priority. Still, by the mid-1990s, the internet and computer hardware had evolved enough to allow primitive 2D graphics to be rendered online. This enabled the creation of graphical MUDs ─ games that merged text-based multiplayer worlds with graphical interfaces.

Classic MUDs like AberMUD were entirely text-based, requiring users to imagine the environment through written descriptions; graphical MUDs let users directly control an avatar and visually see the world’s layout and other players. Titles like The Realm Online, Nexus: The Kingdom of the Winds and Meridian 59 pioneered this concept in the mid-90s and while tile-based 2D graphics were simple by today’s standards, they represented a huge leap in immersion at the time. Of these, Meridian 59, launched in 1996, was the most influential early graphical MUD: it featured a medieval fantasy setting, user chat, guilds, PvP combat, magic spells, and questing. Players could explore forests, dungeons and towns in a graphical form for the first time.

Meridian 59 demonstrated that taking the text-based MUD concept into graphical 2D form could work smoothly and attract larger, more mainstream audiences compared to all-text interfaces. At its peak, Meridian 59 had over 15,000 subscribers ─ very sizable for an online game at the time, indicating a broader appetite beyond just hardcore gamers. It is therefore not very surprising that the term “graphical MUD” was soon changed into MMPRPG – massive multiplayer role-playing game. This new term should very soon be shaped into its final form, in big parts by the famous creator of the Ultima series, Richard Garriot, and the release of Ultima Online.

The Ultima series started in the early 1980s with Akalabeth: World of Doom on the Apple II. It established the lore and fantasy world of Sosaria, which would later be built upon by Ultima I in 1981, with a full story about defeating the evil wizard Mondain who aims to rule the world. The CRPG gameplay let you explore dungeons and towns but, as the series progressed, the world became more immersive with richer stories and innovations like day/night cycles and pseudo-3D graphics. Ultima IV: Quest of the Avatar, released in 1985, was a major landmark for the Ultima series and RPG genre overal,l due to its narrative depth and focus on moral philosophy and ethics. The game introduced a complex moral alignment system based on virtues like honesty, compassion, valor and justice that shaped gameplay and broke free from typical “defeat the villain” RPG tropes, with a bold goal of ascending as a moral exemplar and avatar. The open world structure encouraged exploration and nonlinear progression through the world of Britannia, all the while deep conversational mechanics with NPCs, along with day/night schedules, made the world feel alive.

By Ultima VII in 1992, the re-branded world of Britannia was brought to unprecedented life through details like interactive environments and complex NPC schedules with narrative depth that set a benchmark. 1992 was also the year that Richard Garriott’s company Origin Systems was acquired by Electronic Arts. By the mid-1990s, EA saw the success of early online games like Meridian 59 and the growing popularity of multiplayer experiences. They pressured Origin Systems to take their acclaimed Ultima single-player RPG series into this new market, despite Garriots resistance. In an interview, Garriot admitted that he was deeply skeptical about an Ultima online world at first, feeling it would dilute the narrative focus of the franchise. Once committed to the project though, Garriott warmed up to its potential. He worked with Starr Long on conceptualizing Britannia as a living virtual world, when development began in 1995 under the codename Multima.

Finally released in 1997, Ultima Online did not achieve the “first 3D” milestone but its execution represented a quantum leap forward in scale, polish, and commercial success. Previous 3D titles were essentially graphical MUDs, while Ultima Online created an immersive living world shared by a true massive multiplayer fanbase. Britannia was brought to life with immersive natural environments like forests, rivers, caverns that players could explore freely in first-person 3D perspective. Thousands of simultaneous players could interact in this shared world in ways not possible before, collaborating, competing, trading. The “massively multiplayer” scale was unprecedented and made Ultima Online become the first “true” massive multiplayer online role-playing game, or MMORPG.

Not only could players choose and customize diverse classes and skills beyond just combat and adventuring, but also invest into crafting, cooking, lumberjacking, even music composition. Complex player-driven dynamics like property ownership, crime, guild formation, and medieval style government proved to be highly immersive and many a tale were spun in Ultima Online. One of the most famous might be the Assassination of Lord British, Richard Garriots pseudonym since the inception of Ultima, and his normally unkillable character in the world of Ultima Online. The newly crowned king of online games generated mainstream buzz and appeal far beyond existing niche online RPG audiences of the time and eventually garnered over 100,000 active subscribers. This subsequently drove massive infrastructure investment as networks strained to support the concurrent player loads ─ and the ones that were yet to come.

Future MMO developers could clearly see the potential for virtual worlds, where emergent player-created narratives could thrive alongside developer-crafted stories. Ultima Online’s runaway success validated the MMORPG format and directly inspired many subsequent virtual worlds like Dark Age of Camelot and Asheron’s Call in the late 90s. However, in 1999, a game called Everquest is going to take the world of massive multiplayer online games by force. This is where our next episode of From Pong to Ping is going to pick up.